Most of my day is spent thinking about invisible things. Well, not quite invisible, just reeeeally small. The tiny things I spend every waking hour (and most sleeping ones) obsessing over are the following: bacteria, DNA, and impossibly small wasps. And yes, I think of them all at the same time. I study symbiosis. Here is what The Oxford English Dictionary has to say about symbiosis:

noun (plural symbioses ˌsɪmbɪˈəʊsiːzˌsɪmbʌɪˈəʊsiːz)

[mass noun] Biology

1. Interaction between two different organisms living in close physical association, typically to the advantage of both.

Symbioses are common. We are in a symbiotic relationship with all the bacteria in our guts, for example. My favorite symbiotic relationship is between a bacterium known as Wolbachia, and a very small wasp known as Trichogramma.

noun (plural symbioses ˌsɪmbɪˈəʊsiːzˌsɪmbʌɪˈəʊsiːz)

[mass noun] Biology

1. Interaction between two different organisms living in close physical association, typically to the advantage of both.

Symbioses are common. We are in a symbiotic relationship with all the bacteria in our guts, for example. My favorite symbiotic relationship is between a bacterium known as Wolbachia, and a very small wasp known as Trichogramma.

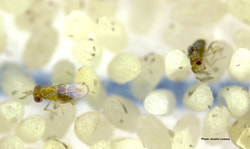

The image that often comes to mind upon hearing the word "wasp" is that of a large, black and yellow insect that stings and lives in a nest with others of its kind. Trichogramma don't fall into this category: they are less than half of a millimeter in length, they prefer the solitary life, and they wont sting you. In fact, most wasps are more like Trichogramma, we just don't notice them. And while they may not sting you, the females will sting something. That something might be a tree, another insect, or even another wasp. When a small Trichogramma stings its preferred sting-ee (moth and butterfly eggs) it is in fact laying an egg. Once Trichogramma inserts an egg, the wasp will develop inside of the moth egg, eating what would have hatched into a caterpillar. A week or two later, instead of a wee caterpillar, an adult wasp hatches out of the egg shell. This is known as parasitism; Trichogramma is a parasitoid wasp. Other species of parasitoid wasps will lay their eggs in or on caterpillars, spiders, grubs, maggots, eggs of other insects, you name it. There are estimated to be more than half a million species of parasitoid wasps, each with their own particular preferences of where to lay eggs. There is a whole world of these tiny creatures out there that most are not aware of.

In the laboratory, we can watch all this happen.

In the laboratory, we can watch all this happen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed