By: Eric Gordon, Graduate Student Researcher, University of California, Riverside

I work on a groups of bugs that aren't very common or well known. Not only are they cryptically colored but you can only find them in the tropics where they're not particularly abundant. This combination means they happen to be pretty infrequently collected and observed even less often. Even if you did spot one, you’d probably have no idea that these cryptic bugs can possess such interesting biology and behavior

The insects I’m talking about are assassin bugs in the subfamily Salyavatinae. At least one species, Salyavata mcmahanae, has been comparatively well studied. Check out this amazing documentary clip below.

I work on a groups of bugs that aren't very common or well known. Not only are they cryptically colored but you can only find them in the tropics where they're not particularly abundant. This combination means they happen to be pretty infrequently collected and observed even less often. Even if you did spot one, you’d probably have no idea that these cryptic bugs can possess such interesting biology and behavior

The insects I’m talking about are assassin bugs in the subfamily Salyavatinae. At least one species, Salyavata mcmahanae, has been comparatively well studied. Check out this amazing documentary clip below.

That moving amalgam of dust is actually a nymph (or immature) of one of these assassin bugs and that dust is made up from the same material as the termite colony and seems to chemically disguise it from the termites. These specialist bugs can “fish” for termites over and over up to 31 times in a row and go unnoticed by termite soldiers. Scientists have only ever recorded this species feeding on one particular species of nasute termite, Nasutitermes corniger.

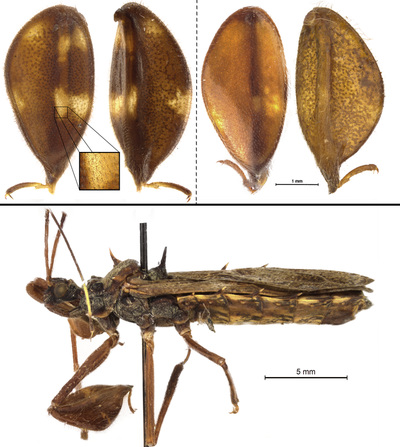

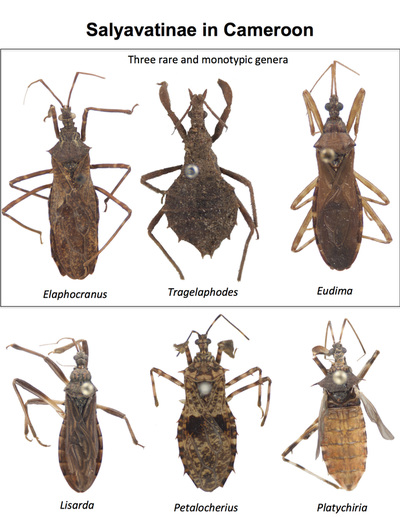

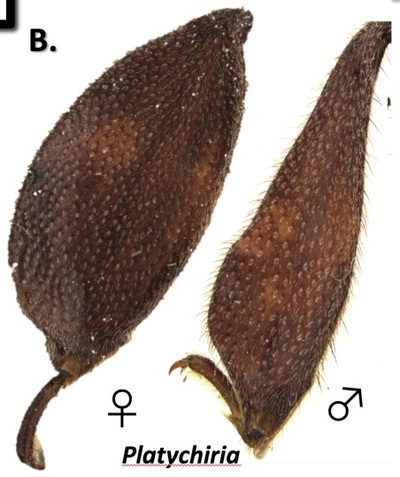

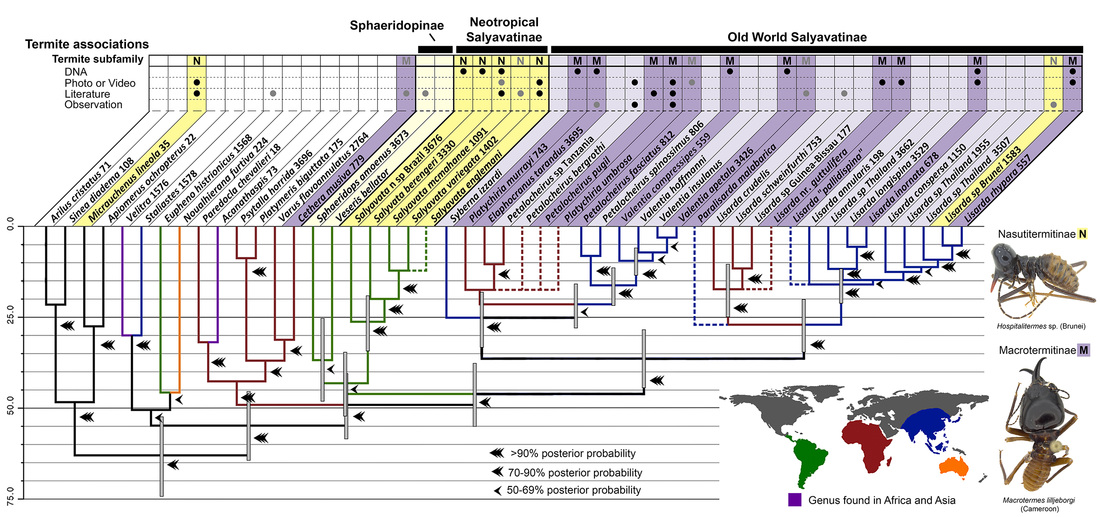

The genus Salyavata is the only salyavatine that you can find in the New World, but there’s a whole group of other genera in Africa and Asia; check out the diversity of the group in the pictures below. You can see that some have strange enlarged fore legs often covered with unique hairs, and that sometimes the females possess larger forelegs than males by quite a bit. Intriguing right? Unfortunately, we have no idea why (in an evolutionary sense) and no one has ever observed these bugs “use” their uniquely modified legs. Like S. mcmahanae, a meager handful of species in Africa and Asia have literature reports recording them as being observed near or feeding on termites, but unlike S. mcmahanae, none has ever had any special study devoted to it. Another subfamily, Sphaeridopinae (also pictured), is thought to be a close relative of this family and might specialize on termites, as one species has been caught near a termite nest and fed on those termites in captivity (P. Wygodzinsky pers. comm. in McMahan [1982]).

The genus Salyavata is the only salyavatine that you can find in the New World, but there’s a whole group of other genera in Africa and Asia; check out the diversity of the group in the pictures below. You can see that some have strange enlarged fore legs often covered with unique hairs, and that sometimes the females possess larger forelegs than males by quite a bit. Intriguing right? Unfortunately, we have no idea why (in an evolutionary sense) and no one has ever observed these bugs “use” their uniquely modified legs. Like S. mcmahanae, a meager handful of species in Africa and Asia have literature reports recording them as being observed near or feeding on termites, but unlike S. mcmahanae, none has ever had any special study devoted to it. Another subfamily, Sphaeridopinae (also pictured), is thought to be a close relative of this family and might specialize on termites, as one species has been caught near a termite nest and fed on those termites in captivity (P. Wygodzinsky pers. comm. in McMahan [1982]).

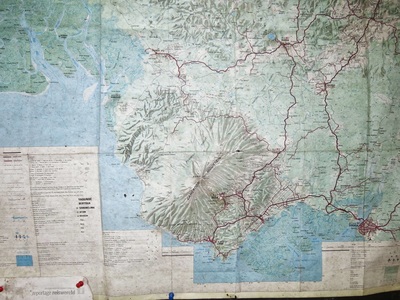

Recently I traveled to Cameroon in an attempt to collect some of these assassin bugs. Cameroon hosts an exceptional diversity of these bugs in a relatively small area and I hoped to collect quite a few species along with conducting some behavioral observations to see if I could confirm whether or not at least some Old World members of the group were also termite specialists.

We set out to collect in two areas, Mt. Cameroon, the tallest mountain in West Africa, and Korup National Park, along the border with Nigeria. Below is a selection of pictures from the trip and even more pictures can be viewed here and here if so inclined.

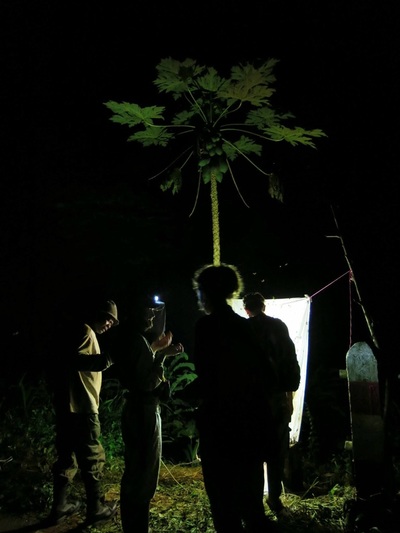

On our second to last night in Korup, we set up a light trap at a bridge in the outskirts of Mundemba. We had an exceptionally good night and ended up with quite a few different reduviid species, including ~20 individuals of Centraspis ducalis, a millipede feeding assassin bug. By the 10th or so, we were bored of just collecting the same bug over and over…so we started to play around with them a little bit. We discovered that they can spray defensive secretions (potentially uniquely among assassin bugs) and that the secretion can even burn/irritate skin. Check out the video below!

Another highlight of that night was finding this giant assassin bug, Psytalla horrida, not at the light, but nearby sitting on a post on the bridge. This is the largest assassin bug species in the world and was on our bucket list to collect in Cameroon. Check out the stridulation behavior, rubbing its labium on the ridged prosternal groove, in the video below. This assassin also has a very noxious defensive secretion but wasn’t capable of aerosolizing it.

Unfortunately, no salyavatines ended up coming to the light trap that night or any other night. And soon…. it was our last day of collecting and I still hadn't seen a single termite assassin bug after two weeks of collecting and intently searching around the very abundant varieties of termite colonies. We were returning back from the Korup rainforest for the final time on an unusually clear and sunny day after taking down our Malaise traps and were on a time crunch to get back to our guide, Chief Adolfo’s, house for dinner. My labmate Michael and I were almost back when we noticed a faint sort of drumming sound in the forest. Check out the video below.

These termites were huge. Our guide later said we hadn’t seen them on any of our previous forays because it had been raining too hard for them to surface and forage. They didn’t have an overt nest either but surfaced from multiple holes in the ground, probably indicating they live in a subterranean colony. I later identified them as Macrotermes lilljeborgi, which is one of the largest termites in the world and is relatively poorly studied, probably because of its remote habitat and cryptic colony. We were (or at least I was) frantically searching around these termites and collecting a few of them when Michael spotted it.

Finally! And even though it was just one specimen, the specimen belonged to a very rare species (Elaphocranus tarandus), the only member of a monotypic genus, known from very few specimens in entomological collections across Europe. I grabbed it and threw it in a vial before I could observe whether it had been eating the termites we found it next to. Hey, at least we found it next to termites right? Unfortunately, we were very pressed on time so we couldn’t linger around to see if we could find any more or observe any behavior.

It was only after returning back to the states that I really regretted not having been able to watch the bug for at least a little bit before collecting it. We might never really know if collecting the bug right next to a trial of foraging termites was a big coincidence or maybe it had really been stalking its prey. This happens to be a big problem for biodiversity science in general. A through understanding of the natural history and behavior of all species on earth is going to be very hard to achieve, especially for tropical arthropods where dedicated and repeated observation of individuals in their natural environment can be difficult, inefficient and expensive. Even worse, the number of species of arthropods on earth is staggering, especially in the tropics, and not all species can be expected to have devoted natural history studies within any reasonable time period.

After spending some time thinking about this problem, I decided to try and find a solution, at least partly and at least for my group, where all the members were suspected to be specialist termite predators. I designed three pairs of primers, or small chunks of DNA, that matched the sequence of termite genes but not the corresponding gene in assassin bugs. Then tried to amplify small chunks of termite DNA out of the guts of ~50 specimens of Salyavatinae from around the world including the E. tarandus specimen I collected in Cameroon. This had the potential to definitively prove that that specimen had been feeding on termites!

The extraoral digestion and liquid diet of assassin bugs probably hastens the degradation of DNA in gut contents (as has been noted in other related sucking predators) so I wasn’t as successful as theoretically possible, but overall, I found out that quite a few specimens seemed to have been recently feeding on termites. Some of the genes I amplified were even variable enough to be able to be matched down to a species of termite, as long as someone had catalogued that DNA sequence before on GenBank. I also found that my success rate for adult females was higher than for adult males in line with the theory that females may be consuming more as adults for egg production. I also used some other primers for two hyperdiverse insect orders to check to see whether the bugs might be generalists.

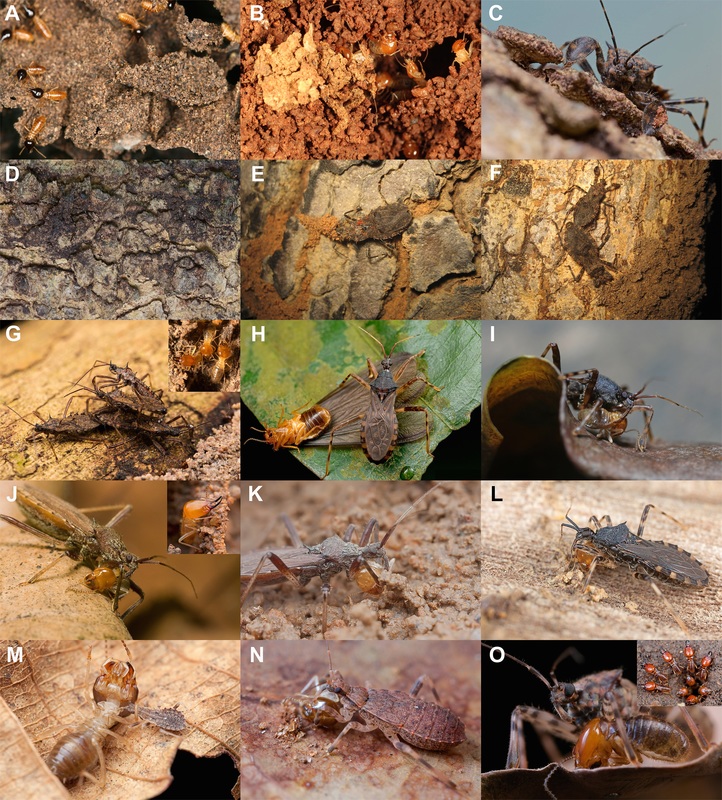

I gathered even more evidence of termite specialization by these bugs using another online resource: flickr.com. Everyday hundreds of potentially scientifically valuable images are uploaded to flickr and other online resources and this represents a huge untapped resource for scientific studies. There are a growing number of photographers who are based right in the tropics and have the ability to document natural history relatively inexpensively. Check out some of the fantastic photographs below.

After spending some time thinking about this problem, I decided to try and find a solution, at least partly and at least for my group, where all the members were suspected to be specialist termite predators. I designed three pairs of primers, or small chunks of DNA, that matched the sequence of termite genes but not the corresponding gene in assassin bugs. Then tried to amplify small chunks of termite DNA out of the guts of ~50 specimens of Salyavatinae from around the world including the E. tarandus specimen I collected in Cameroon. This had the potential to definitively prove that that specimen had been feeding on termites!

The extraoral digestion and liquid diet of assassin bugs probably hastens the degradation of DNA in gut contents (as has been noted in other related sucking predators) so I wasn’t as successful as theoretically possible, but overall, I found out that quite a few specimens seemed to have been recently feeding on termites. Some of the genes I amplified were even variable enough to be able to be matched down to a species of termite, as long as someone had catalogued that DNA sequence before on GenBank. I also found that my success rate for adult females was higher than for adult males in line with the theory that females may be consuming more as adults for egg production. I also used some other primers for two hyperdiverse insect orders to check to see whether the bugs might be generalists.

I gathered even more evidence of termite specialization by these bugs using another online resource: flickr.com. Everyday hundreds of potentially scientifically valuable images are uploaded to flickr and other online resources and this represents a huge untapped resource for scientific studies. There are a growing number of photographers who are based right in the tropics and have the ability to document natural history relatively inexpensively. Check out some of the fantastic photographs below.

(A) Camouflaged Salyavata mcmahanae nymph with Nasutitermes sp. in Costa Rica (Gernot Kunz). (B) Camouflaged Platychiria umbrosa nymph with Macrotermes sp. in South Africa (Steen Dupont). (C and D) Petalocheirus schoutedeni in Katavi National Park, Tanzania showing expanded protibial structures and crypsis on bark (Paul Bertner). (E and F) Petalocheirus bergrothi female feeding on termite through mud tube and adults mating near covered termite trails in Katanga, Dem. Rep. of Congo (Bruce Gill). (G) One female and three male Petalocheirus fasciatus mating near shelter tubes in Siem Reap, Cambodia. Inset of Macrotermitinae (cf. Odontotermes) associated with tubes. (H) Lisarda inornata female with Macrotermitinae alate in Singapore (Nicky Bay). (I) Lisarda inornata feeding on Macrotermitinae worker in Singapore (Melvyn Yeo). (J) Lisarda rhypara feeding on Macrotermes worker in Singapore. Inset shows conspecific soldier morph with unique hyaline tip of labrum found only in Macrotermes soldiers (Melvyn Yeo). (K) Lisarda rhypara male (separate photo clearly shows pygophore) feeding on Macrotermitinae worker in Malaysia (Hock Ping [Kurt] Guek). (L) Lisarda ‘‘pallidispina” female feeding on Macrotermitinae worker in Singapore (James Koh). (M) Lisarda nymph feeding or scavenging on a Macrotermitinae worker in Singapore (Melvyn Yeo). (N and O) Lisarda nymph and adult (species nr. L. gutuliffera) feeding on Macrotermes worker (solider with hyaline labrum tip pictured separately) in Udzungwa mountains, Tanzania (Paul Bertner).

By combining these sources of evidence, I was able to more than triple the number of documented termite associations in this group and provide a substantial amount of evidence that this entire clade may be entirely composed of termite specialists. No source whether literature records or photographs or DNA evidence has ever recorded a member of this subfamily feeding on or even associated with another group of prey. The evidence I gathered also indicated that subclades of termite assassins seemed to be specialized on subgroups of termites. Those in the New World seemed to only feed on nasute termites, while those in the Old World only seemed to eat termites in the subfamily Macrotermitidae despite nasute termites being both present and abundant in Africa and Asia. Hopefully new data will continue to be gathered and can either corroborate or refute this hypothesis! If you want to read even more about the study check out the paper that has just been officially published.

I’d like to once again thank all the fantastic photographers and other naturalists for their permission to use their photos and their contribution to this research, and if you’d like to see even more great photos please visit their websites:

Nicky Bay (http://sgmacro.blogspot.com/), Paul Bertner (https://pbertner.wordpress.com/), Steen Dupont, Bruce Gill, Stéphane de Greef (http://www.stephanedegreef.com/), Hock Ping [Kurt] Guek (orionmystery.blogspot.com), John Hash (https://twitter.com/phoridfly), James Koh (https://www.flickr.com/photos/jameskoh/), Gernot Kunz (http://gernot.kunzweb.net/), Steve Marshall, Aaron Pomerantz (https://twitter.com/aaronpomerantz) and Melvyn Yeo (http://melvyn-yeo. blogspot.com/).

My name is Eric Gordon and I'm a graduate student researcher at the University of California, Riverside who works with Christiane Weirauch and systematics of assassin bugs and the bacterial symbionts of Heteroptera.

Gordon, E.R.L., Weirauch C. 2016 Efficient capture of natural history data reveals prey conservatism of cryptic termite predators. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 94: 65-73.

McMahan, E.A., 1982. Bait-and-capture strategy of a termite-eating assassin bug.

Insect. Soc. 29, 346–351.

Nicky Bay (http://sgmacro.blogspot.com/), Paul Bertner (https://pbertner.wordpress.com/), Steen Dupont, Bruce Gill, Stéphane de Greef (http://www.stephanedegreef.com/), Hock Ping [Kurt] Guek (orionmystery.blogspot.com), John Hash (https://twitter.com/phoridfly), James Koh (https://www.flickr.com/photos/jameskoh/), Gernot Kunz (http://gernot.kunzweb.net/), Steve Marshall, Aaron Pomerantz (https://twitter.com/aaronpomerantz) and Melvyn Yeo (http://melvyn-yeo. blogspot.com/).

My name is Eric Gordon and I'm a graduate student researcher at the University of California, Riverside who works with Christiane Weirauch and systematics of assassin bugs and the bacterial symbionts of Heteroptera.

Gordon, E.R.L., Weirauch C. 2016 Efficient capture of natural history data reveals prey conservatism of cryptic termite predators. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 94: 65-73.

McMahan, E.A., 1982. Bait-and-capture strategy of a termite-eating assassin bug.

Insect. Soc. 29, 346–351.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed