by Erica Sarro, Ph.D. Candidate

Twitter: @erica_sarro

Each spring, as the snow begins to melt and warm weather approaches, young bumble bee queens emerge, one by one, from underground burrows. They’ve waited out the winter in these burrows. These queens likely haven’t eaten since fall, so they quickly begin searching for their next meal. In Yosemite, like in much of the western United States, spring queens feed primarily on the pollen and nectar from manzanita flowers. Manzanita is one of the earliest and most abundant flowering plants in the region. It is at large stands of manzanita in early May of 2019 that my field assistants, Claire and Charlie, and I searched for queens of the yellow-faced bumble bee, Bombus vosnesenskii.

Twitter: @erica_sarro

Each spring, as the snow begins to melt and warm weather approaches, young bumble bee queens emerge, one by one, from underground burrows. They’ve waited out the winter in these burrows. These queens likely haven’t eaten since fall, so they quickly begin searching for their next meal. In Yosemite, like in much of the western United States, spring queens feed primarily on the pollen and nectar from manzanita flowers. Manzanita is one of the earliest and most abundant flowering plants in the region. It is at large stands of manzanita in early May of 2019 that my field assistants, Claire and Charlie, and I searched for queens of the yellow-faced bumble bee, Bombus vosnesenskii.

Bumble bees can fly at near freezing temperatures. They can heat their body by vibrating their flight muscles, which enables them to fly in conditions where few other insects can. Here, Claire and Charlie search for queens in a manzanita stand (and find some!) at 45 °F with snow on the ground and heavy fog.

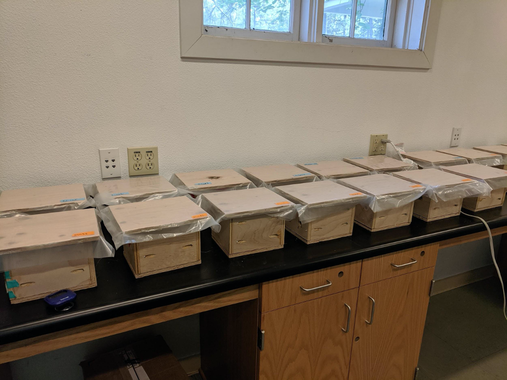

Once the queens were collected, we brought them back to the lab at the University of California Natural Reserve System Yosemite Field Station. We set them up in nest boxes so that they could start their own colonies. In the wild, these queens would find a suitable nest site (likely an abandoned rodent burrow or other underground hollow) and lay their first set of eggs. Instead, our queens laid these eggs in cotton-lined boxes in the lab. We fed the queens sugar syrup (as a substitute for nectar) and pollen to sustain them while they incubated their eggs and those eggs hatched into larvae.

Once the queens had larvae that were a few days old (and thus had an established nest that they would be motivated to return to in order to feed their brood), the real experiment began. We tagged each queen with a radio frequency identification (RFID) tag (more on this later) and put their nests out into the field. We placed the nests within mesh tents over sections of meadow, somewhat like a natural, open-air greenhouse. These tents enabled us to control which flowers the queens had access to. Our basic question was: Do queens adjust their food collection (foraging) behavior in response to different resource environments? Essentially, if we put some queens in tents with sparse flowers, and some queens in tents with lots of dense flowers, will the queens in these different environments forage differently? We predicted that queens in areas with sparse flowers would forage more often and for longer periods of time than queens with dense flowers. This is because queens with sparse flowers would have to work harder to access the same amount of nutrients as those with dense flowers. This is an important question to know the answer to, because the more time queens spend collecting food, the less time they have to incubate their brood. In bumble bees, the more frequently larvae are incubated, the faster they develop. So, if a queen has less time to incubate her brood because she has to work harder to collect food, her offspring will take longer to develop. That means her colony will grow more slowly. Bumble bee colonies only live one season. If development time is slowed down and the colony gets a late start, this may limit the ultimate growth and success of the colony.

We connected each nest box entrance to an RFID reader box. The RFID readers recorded the time and duration of every foraging trip each queen took. When the queen passed through the RFID reader box, it read the unique RFID tag affixed to her thorax and recorded a precise timestamp that we could analyze later.

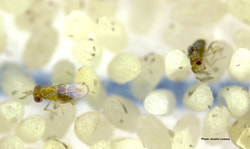

RFID-tagged B. vosnesenskii queen resting outside the RFID reader box. You can see the small, white RFID tag attached to her thorax. Bumble bees use visual cues to recognize their nest entrance, so Claire decorated the box in the hopes that the queens would more easily recognize the entrance to their own nest. This queen was in a “dense flower” tent with abundant lupine, mountain dandelion, and other flowers.

We also monitored the tents for several hours each day. Any time we saw that a queen was out and foraging, we video recorded the queen’s foraging bout. This would enable us to analyze the amount of time each queen spent visiting flowers of specific species, flying between flowers, resting outside the nest, or carrying out other behaviors. This information would help us better understand queen foraging. We repeated this at multiple field sites with different queens.

We were successful in collecting and rearing the queens, finding flower-filled meadows and setting up the tents, and working out the kinks with a new RFID system to record queen movements. Unfortunately, as with most fieldwork, we did run into some unforeseen obstacles. Particularly, we learned that some queens don’t take kindly to being in tents. They often flew into the mesh sides or perched on the ceiling or walls of the tent for hours at a time. Some even abandoned their nests altogether and spent the nights outside on the ground! Unfortunately, we weren’t able to answer the questions we set out to answer this season. But we learned an important lesson here: wild animals are wild, and we can’t always predict how they’re going to respond to the things we throw at them. That’s science. Things don’t always go as planned. You can do everything right, but if your study organism doesn’t like it, there’s often little you can do. But with the RFID system up and running, and the queen collection and rearing down, I am excited to take these skills and apply them to new and related projects to better understand the foraging biology of early nesting bumble bee queens.

Queens only forage early in the season. Once they successfully rear their first set of offspring to adults, those daughters (they’re all female at this point in the colony!) will take over the foraging and brood care responsibilities so that the queen can focus on laying more eggs and growing the colony. In the early nesting stage, the queen is the sole forager, and the actions she takes can make or break the success of her colony. Partly because the queens only forage for a short time, we know very little about what they forage on, when they forage, how frequently and for how long they forage, and how they make these foraging-related decisions. With future research, I plan to further investigate queen foraging behavior to better understand how queens make these decisions, and how these actions impact colony development and success. See you next field season, queens!

Queens only forage early in the season. Once they successfully rear their first set of offspring to adults, those daughters (they’re all female at this point in the colony!) will take over the foraging and brood care responsibilities so that the queen can focus on laying more eggs and growing the colony. In the early nesting stage, the queen is the sole forager, and the actions she takes can make or break the success of her colony. Partly because the queens only forage for a short time, we know very little about what they forage on, when they forage, how frequently and for how long they forage, and how they make these foraging-related decisions. With future research, I plan to further investigate queen foraging behavior to better understand how queens make these decisions, and how these actions impact colony development and success. See you next field season, queens!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed